Hello @flyunicorn,

Yes, I know it might sound confusing to use the output from a randomly initialized Q network for part of the label to improve the Q network itself.

I think the first step to get away from this confusion is that we don’t focus on the second term but we focus on the first term because it is a piece of truth we inject to the network during the training process. With this, we know something true is being used to improve the Q.

Then the second step would be not to fix our eyes on one training example, but more. I will use two here:

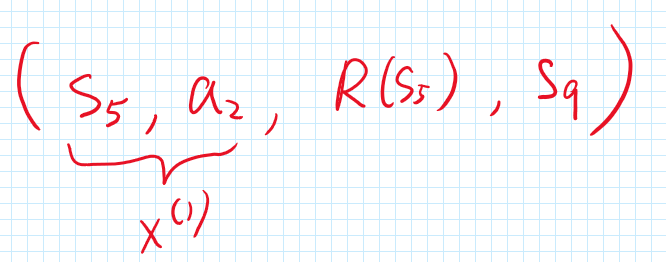

Let’s say we have the following tuple to create (x^{(1)}, y^{(1)}):

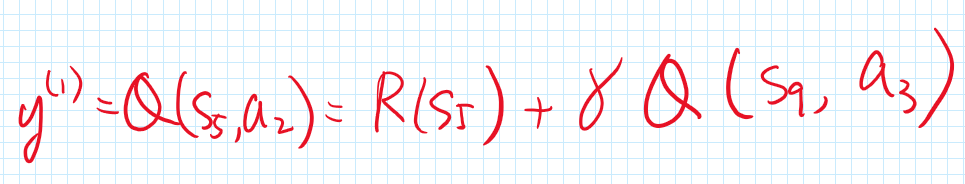

and with that we compute the following label, assuming that a_3 is the best action:

Now, you might think this label y^{(1)} is bad because you don’t trust Q(s_9, a_3). However, what if I tell you a piece of new fact that the Q-network had been trained with the following example (x^{(0)}, y^{(0)}):

Would this piece of new information give you a little more confidence on the label y^{(1)}? Because in this case, (if the network had learned (x^{(0)}, y^{(0)}) perfectly) we can substitute y^{(0)} into y^{(1)} and we have:

Now, I will say y^{(1)} looks better than before because even though I may not trust Q(s_{21}, a_7), its significance has been dampened by gamma squared. You know, gamma is between 0 and 1 and when you square it, it’s only going to be smaller.

If you repeat this thought process for n times, you can imagine that the untrustworthy Q get diminished by \gamma^n.

The idea here is that, you won’t expect any major improvement in the first few rounds of training, but after some rounds, the previously trained example (like y^{(0)}) will kick in and make new example’s label (like y^{(1)}) better.

Therefore, two take-aways for how to get away from the confusion:

- remember we have the first term (the reward) which is a piece of true information.

- don’t stare at just one training example, but think about how previous examples and gamma can help.

Cheers,

Raymond